Table of Contents

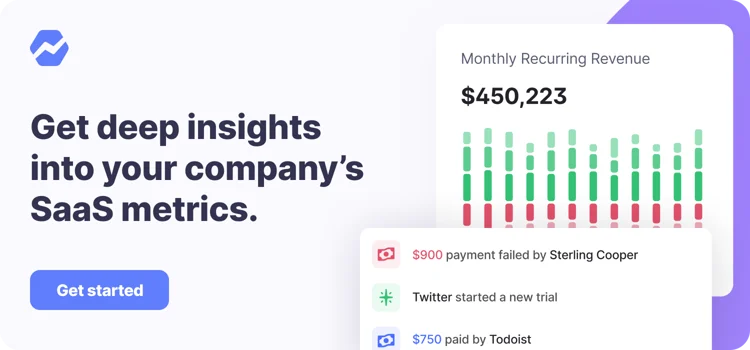

Founder Chats is brought to you by Baremetrics: zero-setup subscription analytics & insights for Stripe, Recurly, Braintree and any other subscription company!

Like this episode? A rating and a review on iTunes would go a long way!

About Jeff Solomon:

Jeff is a 6x founder and has been in the startup scene for most of his career. He has done just about every role from CEO to Chief Janitor, Head of Product to Marketing Lead.

He has deep expertise in Saas, Content Marketing, SEO, Mobile Apps, Startup Accelerators, Lead Generation, UX, Angel & Seed Funding, B2B Software, Enterprise Sales and Bootstrapping. And he’s been writing content on these topics for most of his career.

Jeff co-founded Amplify, Startup Accelerator (5 funds, $50MM raised, 10x exits) and Velocify (sold in 2017 for $128MM). He has raised $35MM+ in venture capital. And he’s had one startup fail miserably. He’s angel invested in a dozen companies. Moreover, Jeff has seen over 3,000 startups apply to Amplify and been pitched by hundreds of entrepreneurs. And he’s helped raise more than $50MM in venture funding for his companies.

Jeff is currently growing Markup Hero, a screenshot & annotation SaaS tool and has been teaching high school entrepreneurship for 6 years. He recently launched a comprehensive online customer development course available on Udemy and is one of the top 10 expert advisors on the popular advisor platforms Clarity.fm with over 500 calls and 350+ 5-star reviews.

About Markup Hero:

Capture ideas, communicate clearly, and save time with Markup Hero a file annotation and screenshot tool. All you need without the bloat; made for Mac, Windows, Linux, Chrome and Mobile Web.

Founder Chats listeners get 3 months free on an annual plan with the code X84BB9 🎉

Sign up for Jeff’s course: Launch + Grow Your Business with Startup Customer Development

Customer Development is the single most important skill entrepreneurs need to be successful. Whether launching a startup for the first time, or you’ve tried and failed before, or your existing business is building out a new product — customer development is the critical activity you cannot skip.

To get a discount on the course, get in touch with Jeff at his personal website or on Linkedin.

Episode Transcript:

Brian Sierakowski: Welcome to Founder Chats by Baremetrics where we chat with founders and hear how they started and grew their businesses. This week, I talk with Jeff Solomon, co-founder of Markup Hero. In this episode, we talk about Jeff’s story, his early entrepreneurial efforts navigating a challenging time in school, all the way through launching new, physical, and digital markets. Enjoy!

Hey Jeff, welcome to the podcast.

Jeff Solomon: It’s great to be here. Thanks so much for having me, Brian.

Brian Sierakowski: Sure, yeah, my pleasure. How’s your day going so far?

Jeff Solomon: Pretty good. I got to sleep in a little bit today. I had a week where I had to wake up really early every day. I’m not a morning person. I’m just not one of those entrepreneurs that wakes up early. Unfortunately, I’m not that person.

Brian Sierakowski: Got it, yeah, I was just thinking about that today because I’ve had a bunch of 7 and 8:00 a.m. start dates or start times this week. Today, my first meeting was at 10 and so I got to drink a cup of coffee and have some breakfast and kind of chill out a little bit before getting into my day.

It’s a true luxury.

Jeff Solomon: It really is. In the fall, it’s always busier for me because I teach this high school entrepreneurship class and it’s a rotating schedule. Any day that I have class could be a different time, but the last three classes were at 8:00 a.m. So, it’s about 45 minutes away. So, I had to hustle.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, cool. Well, I’m so excited to talk with you. Usually what we do is just kind of walk through your story a little bit and generally the best place to start is the beginning. So, if you wouldn’t mind telling me a little bit about where you got started on your entrepreneurial journey?

Jeff Solomon: Well, it all started back with the lemonade stands. Yeah, I was always entrepreneurial growing up. My dad was not an entrepreneur. He was a warden guy, and he was much more polished and very conservative and did not like to take risks. He didn’t really encourage me to be an entrepreneur, but he did encourage me to explore business.

And so, I did the lemonade stand. I had this little carwash business. I had this little sign making business and so I was always into that, but I never really got mentored in that way. It never was sort of shown that this is an actual path. I was just like, oh, this is a cool way to make some money.

When I was a kid, I was not a very good high school student. Not for lack of trying, just didn’t really fit the mold. When I graduated, my dad said, what are you going to do? And I was like, I have no idea. I graduated with an English degree because I actually started in business and failed economics ironically. And so, I was like, this sucks I’m going to go into English.

I got out and my dad was like, go talk to this buddy of mine. He’s got a company, maybe he can hire you. And I went to work for this guy. He had a plastic manufacturing business. If you ever saw the movie, ‘The Graduate’, that happened to me. I mean, he’s had a famous quote where he says plastics. I don’t know if your readers or listeners know that movie, but it’s a classic line.

Anyway, so I started working there and I was working on their website. This was in 1996 and the internet was kind of popping off at that time. I was getting it, I was exploring that and I really learned a lot about how to build products, and bring them to market their physical products.

I realized that I didn’t like manufacturing because it was really slow. It took a year or longer to get something out. And I really started to find interest in technology and how quickly you could prototype and get things out. I bumped into some people that were starting a startup and I joined them and left that company.

We had a nice little ride. I made a little bit of money and my ego got inflated. I was like, okay, well, I’m going to go start my own thing and this was right at the turn of the internet crash. The first startup, I started with five other founders, so six founders, which is too many, they were all like bros.

They were all friends, one of them was my best friend from high school and another kid was from high school. That company just crashed and burned. I would like to say it was purely because of the internet bubble crashing down. That certainly didn’t help, but it was largely due to the fact that we had no business model.

We were not solving any problem that anyone cared about, which I later learned was kind of important, but that got me started, it got me sort of the taste of what it’s like to hustle and have 10 people working in your living room and all that fun stuff that goes along with building a startup from scratch.

I just continued to work at it and eventually started building companies that actually did solve a problem that people were interested in and needed. And success kind of came from that, but it was a struggle for that first four or five, six years where I failed and then I was bumping around trying to figure it out because no one ever showed me.

I never took any classes, there were not a lot of resources in Los Angeles in the late nineties, early two thousands. I just didn’t know. It was just sort of trial and error and yet, you don’t have to do that today.

Brian Sierakowski: So much easier, I guess it’s a little bit meta because that’s part of the point of this podcast as well.

And you can listen to the path that someone else went through and then they can ideally avoid a lot of the mistakes that you needed to sort of run into headfirst.

Jeff Solomon: Absolutely, yeah, that’s what I love about, what did you do today? I work with a lot of entrepreneurs, I am advising a lot of companies, I teach entrepreneurship to high schoolers ironically at the high school that I went to!

I barely graduated. I had the second to worst GPA in the class. Now they have me back there and I teach this entrepreneurship course. I’ve been teaching it for six years there and that worked out pretty good. Now I get to help these other kids that are kind of like me that are sorta (sort of) like, hey, where’s the path that I can follow because this normal getting A’s and getting into Berkeley path is not working for me.

So, it’s great to kind of participate in that ecosystem now having had some success and experience.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, that’s awesome. I feel like that’s a very common story of the worst student or one of the worst students, you sort of learn that it’s actually sort of the model of school didn’t work quite as well, but they actually go on to, hopefully, , in your case you figured out what was going to work for you.

Then you can kind of go back in and share that. In some way I feel there’s an irony to that, like, hey, I’m going back into the system that dictated that I was bad at this, I got rated poorly and now you’re asking me to come back and actually be an instructor.

But on the other hand, it sort of feels like the appropriate correction that you can’t design, like school is definitely not going to be for everybody. So, it’s so much better that students can see that there is another path and school is certainly not the ultimate predictor of your, of your overall success.

Jeff Solomon: That’s, yeah. I mean, the irony is not lost on me for sure. When I went back there, I had that exact feeling, but I will give this school and other schools credit for realizing that on the one hand they have to conform to some consistent structure in order to scale, it is a business in a way.

And so, you can’t do everything for everybody. So, they have to kind of do that, but they are starting to see, particularly that private schools are starting to see that there, they need to at least let the students explore other paths. And so, when they leave, they know, hey, there are many paths, and you can find other ways.

You may not have seen them all here during your time at this school. But when you get out there, you’re going to have an opportunity to explore a lot of that. And, and so that’s, that was the real motivation for coming back and teaching. It was like, I want to let these kids know that this one path that they kind of subscribed to there, which works for some people, like there are kids that just, get A’s and again, go to Berkeley and become bankers.

That’s still a path, but , for me and for other kids out there, that doesn’t work. I really like that education and teaching and that’s why I built it. I have an online course now that’s basically my semester long class in a two-hour nutshell. That’s a big part of my story, but I did have some success.

It wasn’t all, all hard failures, I finally did find my way to some wins, so it was cool.

Brian Sierakowski: That’s great, yeah. I’d love to kind of take, go back and dig in a little bit along the way for the story of like with the lemonade stands, how successful were the lemonade stands that, did you do well?

Did you make good money with lemonade?

Jeff Solomon: Yes, my lemonade stands really worked well for a number of reasons. First of all, my mom would buy the frozen lemonade containers. And I’ll have to make the lemonade. So, my costs to run the operation were very low. I didn’t have any inventory overhead, so that was cool, but I was very good at marketing, and I didn’t realize, I will pass by a lemonade stand today and they’ll, they’ll be sitting at the stand, and they’ll have a little sign and it’ll be on a side street largely because their parents don’t want them to be on a big street.

But in the eighties, when I was doing this, parents were much more lax with their kids than they are now. So, I was out on a busy street, where they had tons of cars and tons of pedestrians, and I would have signs all over the place and I would like, stand up and hold my sign up.

And I was kind of crazy. And so, people would just have to stop and see what’s going on. Even if they didn’t even know what we’re selling lemonade, they were like, what are these kids doing? So, yeah, so that worked well. I mean, we’d go out and sell lemonade for an afternoon and we’d make 50, 60 bucks, for the two kids that were doing this, which is pretty solid.

So yeah, I was …

Brian Sierakowski: That’s like a million dollars in kids’ money.

Jeff Solomon: When you’re eight yeah or 10 for sure it is, and the eighties too.

Brian Sierakowski: For sure. Yeah, Yeah, It’s like what’s like the relative unit of measure. It’s like, well, how much candy can you buy with $50? Like you can buy enough candy to make you so sick to your stomach. It’s an incredible bounty that you can afford yourself.

Jeff Solomon: For sure and then when I started doing car washes we would go door to door. We had this little cart that we built that had all our gear in it and we’d go door to door on a Saturday and Sunday and we’d make two or $300.

This was more when I was like 13, 14, but that was hard work because we were actually washing cars, but I was making decent money.

Brian Sierakowski: Cool, and did you feel like it’s probably difficult to think back to the time, but you feel like any of those lessons sort of rubbed off on you or was it something that, maybe you didn’t connect the dots on until, until later in your career. It’s like, oh, actually we actually kind of figured a lot of interesting things out.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, I didn’t connect the dots. I think I did gain the learnings, which has actually been my experience up through that first failed startup, I was actually learning a lot during the time that I was seemingly failing, and I didn’t connect those dots until way later.

But as an example, in high school, I actually was learning how to write, it was a very scholastic oriented school and I was getting C’s and sometimes D’s on my papers, but I was actually learning something, and it just didn’t stand out relative to the rest of the students. I just was on the curve perspective. I was on the low end but when I got to college, I started acing my English classes, which is ultimately why I became an English major because it was just the path of least resistance. And I didn’t at the time realize why this is weird, like, this class is easier. Okay. I’ll just do this class.

I actually had learned how to write and compile my thoughts very well. And that particular skill has served me incredibly well throughout my career. I think writing and communicating ideas is a big part of being an entrepreneur and a business person. And so, I was learning and even those days doing the carwash and the lemonade, I did learn how you can approach marketing in different ways or how you can approach sales in a different way.

And how when you walk into someone’s house and they say, no, I don’t want a carwash. I would say, well, what about this? or how about this? or what do you think? I would just try different stuff until I got a yes. And all those skills were starting to implant in me. I didn’t know it. Later, as I started getting more formalized around my business process, like, oh, actually, what?

There were a lot of times where I was practicing this, I just didn’t realize it. So, I think, I did learn a lot, I just didn’t know it.

Brian Sierakowski: Nice, was there any sort of dissonance as you were going through school? Like, hey, you guys are saying that I’m bad at doing these things, but I’m also being successful on the side here.

Did that thought ever occur to you or was it more like did you sort of accept the system, uh, at face value?

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, unfortunately I did accept it as face value. I really had left high school feeling like I’m not that smart, which is unfortunate. And I really want to tell my students now, like try not to do that.

And when I got to college, I applied to 12 colleges when I was in high school because everybody was applying to all these schools. I applied to 12 and they didn’t have online applications at that time. So, I had to write 12 essays and fill out the form 12 times and I only got into one college.

I was like, oh man, this is consistent with my overall negative experience as a student at school. I left feeling kind of dumb and until thankfully when I got to college and I started getting A’s without having to do a lot of work, I realized maybe I wasn’t. So it had a negative impact on me for sure.

And I did not connect like, hey, in my personal life, I’m out here having fun, making some money and doing cool stuff that doesn’t jive with my experience in school. And I didn’t unfortunately have anyone that was sort of telling me that hey, look at this, there’s something good happening here that suggests that your challenges in school may not actually be an indicator of how smart you are or whatever.

So yeah, I did have some, some sad times in that way.

Brian Sierakowski: Sure, yeah, and it kind of sounds like you had the parenting style of your parents which was very similar to the books too. So, they probably weren’t very new age from saying our kids are doing poorly in school, but they’re excelling in other ways.

It’s more like you have to do well in school, if you don’t do well in school, you’re doomed. So maybe there’s a little bit of reinforcement for that kind of line of thinking as well.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, I think so, I think that’s the message I heard thinking back to my mom, she probably was a little new agey.

She certainly tried a lot of things to get me to do well in school. I remember this one time we’d go to tutors or different things. One time, she just was like, we’re going to try this different thing and I went to see this lady. I haven’t thought about this in years. Well, I went to see this lady who lived out in Topanga Canyon in California, Los Angeles.

Kind of like a hip hippy-ish area at the time. And she’s like, oh, we’ve heard some good things. This lady has this box that you’d have to get into. And I don’t know what she told me it would do, but anyway, I go to see this lady. She was nice, but she was hippy-ish and she has this box. It’s like a metal box that’s maybe like eight by eight.

So, you can fit in it, but it’s fairly tight and you close the door, and it has these flashing strobe-light things, and maybe it had some music and you had to sit in there. And essentially, I was meditating, , I didn’t know anything about meditation like I do now. And the idea was to try and clear my mind or whatever, and put me in a better position to do well, but it just felt so weird.

And I felt so odd, but my mom encouraged me to just try this thing and it didn’t really help. I still felt I still had the same results, but she definitely was out there trying whatever she could to get me, but she didn’t, she didn’t know what an entrepreneur was, or she didn’t know how to explain to me, she was just like, hey, I’ll try anything to get this kid to not feel dumb because I know he’s not dumb.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, wow. That’s really, that’s interesting. It’s kinda cool too. I mean, it’s one of those things where you can maybe think about the attempt of like, yeah, I probably could have guessed that putting the kid in the box with the flashlights is probably not going to do it, but there’s something to be said about well, the attempt. I don’t know if you had this feeling, at the time, I’m kind of glad that you have somebody that’s well at least, they’re trying like …

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, sure.

Brian Sierakowski: Not accepting at face value maybe at the time as a kid. You’re like, okay, this is weird. Mom, please don’t please women, like strange women from the valley like don’t put me in boxes I mean more …

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, that was more my thought. But she, in retrospect over time, I built a great relationship with my mom and, and realized that she really was trying to get me to see other paths in her own way. I just didn’t realize it at that time, which I think, when I raise my own kids, I have 12-year-old twins. And so, I use those experiences I desperately want to like, let them know that they’re smart and they can find their way and all those things that took me so long to figure out.

But I also realize that when you’re a kid, you don’t connect the dots nearly as well as you do when you’re an adult. And so, it’s a challenge with kids, and I probably was the same way. Kids aren’t great at indicating the dots got connected. I’d like to say something to my kids and in my mind, I’m looking for Oh dad that’s so awesome. I really connected the dots there. Thanks for doing that for me. That’s what I want to hear, but no, I get, Okay, All right, Cool. Thanks, and so I don’t, I don’t know.

Brian Sierakowski: Oh God. You’re, you’re so lame.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, it’s really interesting to consider what you were going from high school into college?

And do you have, did you have any indication at that time? I know that you found English to be something like, oh wow I can actually get results without what feels like a phenomenal amount of effort. So that’s the direction I want to go. But before you found that. Do you remember what was going on in your mind as far as like, well, what is it that you’re looking for or what might be the direction?

What was propelling you through going from high school into college at that point in time?

Jeff Solomon: Mostly it was just wanting to move on. I don’t have in retrospect, I don’t have this negative experience of high school. I had great friends. Most of my memories are good, which is good.

I mean it’s great that it didn’t destroy my psyche, from a scholastic negative aspect. So, I didn’t have a terrible experience. I just didn’t do very well, and it was challenging, but I was definitely ready to get out and go do something else. And I’d certainly heard and observed and knew that college was more fun, and you could do more stuff and you could be an adult.

And so, I was definitely looking forward to all that stuff. But in terms of what path I was going to go on and as a stepping-stone to my career, I really had no idea. So, at that time I was still like, well, my dad’s a business guy, so I guess that’s what I need to do. So, I’m like, I’ll just go into business.

And I knew like with the lemonade stands and the other entrepreneurial things I had done, I figured it still made sense to go down that path. And so, I started as a business major and like I said, I took macro-economics, and I didn’t like it at all. And I got, I got, I think I got a D or maybe I got an F in that class.

I might’ve gotten an F in that class. And I was like, if this is what business is all about, then I’m not, I don’t like it and …

Brian Sierakowski: Right, yeah, this sucks.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, totally. So, no, I didn’t really know the path. And then I, ultimately, I just found that it was just a great place for me to get decent grades and have a good time. And I just let go, and just enjoyed my life for four and a half years.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, that’s really interesting. It’s like, I think that there’s this kind of meme about people who go to college and, or go to university and they just like to party for four years and, maybe like they, the idea is like they are wasting time or something like that.

And then I think, I don’t know, at least as I’ve sort of looked ahead of like, there’s a really powerful sense of like, when you stop thinking especially again from an entrepreneurial standpoint, there’s like all these things that you should do and you should be doing this and you should get good grades and you should study hard.

It’s like when you kind of tune into like, well, hey, like what do I want to do? And what do I need? Generally, the results are better. And it kind of sounds like that’s something that you had there for as soon as you let go of like, well, this is what I should be doing. And you’re like, well, I can get really good grades and also have a good time and enjoy myself and expand my network.

And probably you weren’t thinking this, but I can expand myself as an individual. It feels like you had a much better outcome than if you said like, no, I must become a business major. I will retake economics over and over again until I eventually get a high enough grade to pass and, and move forward.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, definitely the former was my experience. And I didn’t deliberately think of it that way. It just sort of happened. And I guess, my parents were sort of okay I guess, because I was getting decent grades and they kind of also didn’t really know what was going on there. It was an opportunity for me to explore myself.

That was exactly what I needed. I needed some time to just like, let myself be myself. And that was a key growth element for me as a human being, So ultimately, I think that was the learning that I needed. Maybe other kids need other things, maybe other kids do need the structure in the class and the scholastic element of college.

And I certainly saw those students do well, but yeah, I fell into it, it worked out perfectly. Because I ended up going to the right school, even though I got into one and I had the right experience, and it was a very big party school. I went to Arizona state at that time too.

It was particularly party central. So, I definitely got myself down some paths that were probably not super healthy or definitely were not super healthy. So, I had to unwind some of that later in life. And that’s been part of my story as well, but it definitely was what I needed at that time.

Find who you are and you can get back to what career you’re going to do later.

Brian Sierakowski: That’s really cool, during your college experience, was there any kind of early seeds or looking back, did you see anything that started to say like, oh, well, any experiences of, oh, this is like kind of putting me down a more entrepreneurial path or was it really just like you’ve been saying, we’re gonna get some good grades, we’re going to find ourselves a little bit.

We’re going to have a good time. And then we’re going to face the rest of life when we get to the other side of this college experience.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah. I pretty much kicked the can on my career path at that time, it was almost purely about exploring, being a kid again and just enjoying myself.

Like I said, I did start to really enjoy writing and doing well in those classes. And I started to think like, hey, what does that look like? Where does that fit into my career path? The other thing I learned about English was that it was in the liberal arts college and the liberal arts college lets you take all kinds of other classes that give you credit, including art classes. You could get the same amount of credit for taking a woodshop that you could for taking a Shakespeare. So, I took a lot of those classes too, and I always knew that I was pretty good at working with my hands and building things.

And I got to explore that a lot, I started to have some thoughts like, oh, is there something physical and in building, that will be part of my future. And it, kind of was, I guess, in the first job, the manufacturing business that I worked in, I didn’t actually work on the factory line.

So, I didn’t touch things like that. But I did, there was a good connection between building things into the physical world and building software. You still have to visualize it in your head. And so, I think that skill actually translated really well into becoming a product centric tech entrepreneur. I could really visualize how I wanted something to come together.

And that was the same, whether it was a physical item or a piece of software, what the interface would look like and how a user would go about using this particular product. So that served me very well throughout my career.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, that’s super interesting. I feel it goes back to that kind of thought process of it’s relatively difficult to teach somebody the art side of building a business, like the science side of you can teach somebody accounting and you can teach them finance and you can kind of teach them structures and models, but that, that specific piece around, like what you’re going to have this idea in your head, there’s no shapes or boundaries or anything.

And how do you actually sort of manifest this thought that you have? And that’s like an incredibly difficult thing to how you would teach somebody that if you kind of had the art of manifestation of providing you’re not going to like a wizard college or something like that. It’s going to be very difficult to teach that. So, I’ve heard a similar story a few times and I experienced it too. I have a degree in music and you sort of have all those weird. It’s like, you’re not teaching. Like this is the, this, you are in the business school.

And this is when you have an idea, this is how you actually start. And these are the steps that you follow, but you can put people in situations where on a smaller scale, I think woodshops are a great example. You get a chunk of wood, and you need to transform it into your vision.

And you can kind of like, because it’s physical, you can see the steps along the way and you can get to the end and realize that maybe it sucks, maybe this doesn’t work at all how I want, but I think that’s such a great experience and yeah, I can totally see why that sort of plugs directly back into, like, it doesn’t feel like woodshop is like a part of your entrepreneurial education, but I can, I totally get how that does make a connection. And it gives you those great skills that you can build on from there.

Jeff Solomon: It did, I mean, I could probably do a whole session on mapping the things I did in woodshop to my career. And, one thing that just popped in my head is as you were describing the block of wood converting into something, I did a lot of iterating in woodshop.

So, I would have a vision for something. I would start building it and it would start going someplace that I didn’t like. And then I would change. I would be like, okay, well, I guess if I don’t put this here and I can make that piece look like this, I could actually convert it into this other thing, which I really wasn’t thinking about at first.

And so, I learned a lot about iterating which is something you have to do a lot of as an entrepreneur and building and launching a business. Right? You’ll start with something and then you’ll talk to customers, and you realize that something isn’t going to work as well as you thought it might and you’ll adjust. And so there was that skill being learned at that time, too.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, that’s awesome. And you have to be in a very relatively low stakes environment, you have to say, okay, well, I’ve had this idea and I started down the path and I’ve gotten additional information now. And maybe it’s either going to be harder to get there, or the shape of the wood is not turning into the shape that I imagined.

So, am I going to stick to my original idea and try to figure a way to work around that issue? Or am I going to change the direction that we’re going, based on this new information or some combination of the two, you like to run into that all the time. So, it’s like, it’s incredible that I have an experience where you get to sort of make,

You get to wire those neural pathways in a pretty safe and low stakes way. But then, I’m sure I totally believe that when you run into business situations, the brain is already wired to go down that path and you’ve got reps on that.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, that’s a really good observation. I think if people look at education and college in that way where you’re like, hey, these synaptic paths that your brain builds are applicable to many different things, not just that one use case, there’s probably a ton of stuff that is formed during those times.

And this is a great example of one that for me, that gets reused later in life. That I never thought about, That’s pretty cool.

Brian Sierakowski: Can you think of any other examples not to put you on spot because that was so profound that anything else from that kind of a liberal arts education that sort of has built processes or systems that you just experienced that felt unrelated, but you feel like you can actually implement pretty well at the time, or we can implement that.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, one of the things that pops into mind is I’m pretty good at convincing. And my girlfriend likes to say oh, you’re such a good manipulator and it’s a balance, but in business, you have to be able to get people to see what you want them to see in a way where they are excited and happy and fired up.

You can’t truly just manipulate someone to something that they are mad about after the fact they just do it because they forced you. And I do remember many times in class, particularly these poetry classes that I took, where I had to get the teacher or other students in the class to see the vision I was trying to articulate in a piece of writing.

And so, there was a lot of dialogue and debate in those classes where I learned to get people to come to my side, and see what I was seeing. And that, like I said, that skill’s been hugely beneficial, whether it’s a sales conversation or with investors, getting an investor to say yes is all about, getting them into your camp and seeing the vision that you see, in a way where they’re like, they feel kind of like they figured out that themselves, , and the whole inception thing, if you can incept an investor to, to think they came to the conclusion themselves, like they’re going to be fired up to, to join you on the, on the journey.

And so, I think there was a lot of that. And even with friends just getting people to follow the path that I thought was going to be the most fun, or the best night. And people like to hang out with me, and I have a great social network at school because of that.

I always made it a good time for everyone. I was very thoughtful about that stuff and that’s served me well. And in building an organization, in fact, in the first company that was really successful for me, this company, Velocify, which was started in 2004, which is like a CRM business which we sold in 2016.

I was huge on culture at that time. I was trying to build this team of people that literally, I wanted them to think that we were curing cancer and they come into work and like to do work here on cancer day. Like we got to do everything we can to solve that. And so that was kind of, part of my mission is building this incredibly tight knit culture.

And that was kind of sort of the same thing I wanted to do when I was in college. And I had these friends and I tried to get them to sort of join this mission that I had in my mind. And that translated really well to that business. And we did, we had this culture early on when we had like 25 people or less than 25 people.

And people would come into the office, they’d stay till two in the morning and we’d go do activities together. It was like a real family.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, that’s so cool and I can imagine you developing that skill, in poetry class, I feel like I can imagine this sort of not existential, but in an easy sort of esoteric conversations where the professors say, what you’ve written is not a poem.

You’re like, well, first if I need a good grade here and then, the objective was to write a poem. So, I’m going to have probably an extraordinarily wild conversation about the thing that I’ve done here is a poem. And I need to convince you that at some point, we’re just totally outside the realm of like normal human conversation.

But yeah, you’re saying being able to kind of look back and connect the dots, that makes perfect sense that, if you can convince somebody that really doesn’t start on the same page with you, that you’ve written a poem. And you think it’s a poem and you can bring them to your side. That feels like an incredible skill to develop.

And when you actually have something like, hey, this is a good business opportunity, or we are on an important path. And we are in a world where, I mean, I don’t know if what you had written at the time was a poem. I’m going to give you the benefit of the doubt and say, yes, you did write a poem, but there …

Jeff Solomon: What is a poem!

Brian Sierakowski: But yeah exactly, precisely. So, I think when you actually have backup to say like, hey, what we’re doing here at this company is important. It’s probably an even easier scenario that you’re not sort of operating strictly in the world of sophistry.

Jeff Solomon: Yep, yep, I agree. Yeah. I think that was definitely the way it went down there. I think it was a poem, I don’t know, yeah.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah. Let’s see. Actually, let’s bring it up. Well, we’ll put a poll out and say everybody, it’s just a poem or it’s just not a poem. That’ll be the big, ah, that’ll be the big marketing push around this episode. We’ll get some billboards and really go all out on whether or not this was a poem or not.

Jeff Solomon: Ha ha ha, I like it.

Brian Sierakowski: Cool so when you got out of college, was that when you went and began working at the plastics company?

Jeff Solomon: Yeah. So, my dad said, go talk to this guy. And I remember very clearly a good dude who ran this company that was like 50 years old. It was an old stodgy business, but made money.

And he was like, I don’t know what you can do. Your dad’s a really smart guy. I’ll just hire you, and you figure it out. I was like, okay! So that’s how I got my first job. And I had no idea what I was going to do. And I just sort of found my way at that company. And it turned out to be a great proving ground for me because I brought this energy and this fire of this young entrepreneurial kid into a business that had been doing the same thing for the last 50 years.

And most of the people working there were lifers, they had been there for 20, 30 years and they had never seen someone come in, and propose changes? And the cool thing was there were either by way of those people being entrepreneurial in their hearts or just totally burned out and over it.

Brian Sierakowski: Right.

Jeff Solomon: It may have been a combination of the two.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah.

Jeff Solomon: They were open to my suggestions and let me kind of run with, not only ideas for products, but I also launched a ton of products there, some of which sold millions and millions of units. I mean, still sell, but I also implemented a ton of processes because I would just go in and, when you’re manufacturing, there’s a lot of steps, which is the part that I hated?

Because it just took too long. But in those steps, they had developed processes to run them, which you have to do in a business, but those processes were archaic, and they certainly weren’t using technology in it. And even in 96 we had Excel, so I would go there and be like, why are we doing this?

You have this step that goes to this step. That then goes back to that step. Does it logically make any sense to me? And so, I said, well, what if we did it this way? And then a few people would be like, oh no, no, no, we always did it this way. It works, it works. Don’t mess with it but then some of the more senior people were like, Hmmm, okay, yeah, that actually kind of makes some sense. So maybe we’ll try that. And so, a lot of the things that we did, I flipped on their head, and we ended up being way more efficient and making less mistakes. And I just started to learn that, hey, you could change, but that there are many different ways to do things, and some are better than others.

And that was satisfying. I was there for two and a half years, and I learned a ton there and I had some good mentors that I met there that weren’t entrepreneurs, but they would encourage me to just run with my ideas. It was a great place.

Brian Sierakowski: Wow, that’s incredible. I’ve been at a couple of different companies where there was sort of the same setup where these businesses would sometimes, there may be more older businesses stuck in their way and they bring in younger, theoretically credentialed people that are from a good school or whatever from a program. And they, they kind of have had the same sort of setup of like, hey, well, we don’t know exactly what we want you to do, but we want you to kind of come in here. We want the benefit to you if you’re going to get some of this entrepreneurial experience.

And the benefit to us is we’re going to get these young, fresh ideas. And I think that uniformly I’ve seen that fail. I’m trying to think of a scenario where that actually turned out well where that person wasn’t sort of stymied with. First of all, they don’t have the work experience to make good recommendations.

And secondly, they’re given no direction and kind of no authority and people aren’t really interested in changing. I’m curious, like how did that work for you? How did you do that?

Jeff Solomon: I mean, in the thick of it, I didn’t realize I even was, it just seemed, it was more intuitive and logical to do certain things a different way.

And like I said, for whatever reason, it was just the right place at the right time. They were open to a lot of it. Sure. I got blocked some more than I wanted to for sure. But overall, I was able to move through the system when it was just kind of a perfect storm because I think you’re right.

Most of the time it does not work out. Like I’ve observed it from other people that have had similar experiences. Who’ve gone to similar companies where they brought in consultants; that almost never works, where they know that things aren’t broken and they’re like, well, let’s bring in these ‘Bain guys’ to come in and fix it?

And that rarely works, but it was just this, I was just one kid, I was 21 and the next youngest person at the company, other than those working on the factory line or the warehouse, they had younger people there. But in terms of the corporate side the next youngest person was like 35.

And so, there was just nobody bringing those fresh ideas. And, and I guess part of it, one of the interesting things about that business is they were a plastic manufacturing company, but they had a few product lines and one of their product lines, a big one was in the sports collectible space. So, at the time, and even today, they made these baseball card sleeves, the company’s called Ultra PRO and they were the number one sleeve, like best plastic.

What was best well-made, they had a good brand in the market amongst these trading card collectors. Well, at the time, this was like I said, 96, there was a new game and a new movement that was coming at that time, this game, which maybe you’ve played, or I’m sure many of your listeners know about called, Magic: The Gathering.

And this was the very first big, very large collectible card game where it was a card game, but the cards themselves had scarcity. And so, there was a baseball card collectability element to it. And the game was also very good. The mechanics of the game were genius, and that game was blowing up and it was creating this whole new market of gaming / collectible enthusiasts, which still exists today.

Magic gathering still exists. In fact the company was sold to Hasbro where they have grown it, but these guys and the CEO of the company, my dad’s buddy, was intelligent in the sense that he was a smart guy for one, but he was very smart to go out and look for these licensed deals. So, he had deals with MLB.

He had deals with different comic book companies and he saw this trend occurring and he’s like, I’m going to go do a deal with these Magic: The Gathering guys, and see if we can build some products, branded products for that growing sector. And so, when I came in, it was right when they had gotten the licensing agreement done, which is shocking that they were able to do the agreement and meet with those people over at this company in Seattle, and they had nobody that even played the game, let alone understood the game.

And so, when I got there, I didn’t really know the game when I got there, but I was definitely into games and I was like, it really resonated with me. And I was like, oh, this is cool. I learned how to play. And like I was into it, and I loved collecting things. So now they had a person on the team that could go and speak the language.

And basically I became the ambassador of that relationship, and I would go up to Seattle and I would go to trade shows, and they’d send me around the world to all these different shows that we had. I was young. So, I was willing to take the red eye to London for three days to do the trade show.

And I got to travel a lot. So, I was happy, and they were happy because no one else wanted to do that. And I knew that, I knew the product. And so, I was able to really cultivate that relationship. And we built, like I said, some amazing products that are still sold today in that industry and it, and it just continued to grow.

And so that was probably a part of the perfect storm that led them to be like, hey, this guy can actually add value. He’s making, he’s having success for us here in making us real money on this new product line. And if he has ideas to improve processes, like let’s hear him out.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah. That’s incredible. I’m super familiar with Ultra PRO. I have spent a lot of money on magic cards, and I don’t really play, but I mean, I think that sort of speaks to the beautiful business model that they have and all of the, all of the cards that I’ve invested into have Ultra PRO sleeves on them. So, I was not expecting you to say Ultra PRO after you said that it was a plastics company, but that makes perfect sense.

And I think that as you were, as you were talking and going through it, my mind was just kind of spinning of like how that’s just like the, the classic business, we have this kind of genericized, we know we create plastic products, but then, that’s worth something and people need plastic products, but then yeah, you have something like, okay, well we have trading cards and it’s important to protect those cards, but then you have this new wave that comes along and it makes perfect sense because now it’s like something where, they’re not just like displaying the cards they are actually playing with them and the need to protect them is a lot higher.

And I actually, I don’t know sort of what the behaviors are as far as buying sports cards, but I imagine that people who play games like Magic probably buy an order of magnitude more so, have the ability to sell a higher cost product because it’s important to protect them.

And then you’re also selling more of them. So yeah, it totally makes sense being in that spot and wow what a cool experience for you being there, for that, that it feels like just being along for a huge wave and maybe having a little bit of confidence or something to say like, yeah, no, we can totally go after this.

And it sounds like you were also just willing to raise your hand to like, oh, we need somebody to jump on this 20-hour flight and it leaves in four hours, and we need somebody to jump on there and you’re like, yeah, sure. I’ll do it!

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, that was a piece I realized that a lot of people didn’t want to do. And when they got to the trade show, it was like a drag for them. Whereas I had a blast at the trade show and it was a lot of fun and I got to travel. I literally went to like 20 countries over those two years and spent a lot of time on the road.

Because there were so many trade shows, and people knew me, they’d come to the show and be like, hey, is that Jeff guy here? Like what does he get going on? or I show them some new products. I mean I was learning the art of customer development which is a core to my whole entrepreneurial philosophy.

And that my whole class on Udemy is about customer development because I was out there talking with customers and finding out what they needed and then I would bring it back and I’d be like, look, these guys are having this problem and I translated that into a solution. And you’re totally right, as it relates to when you build a business, you have to find a problem that is acute enough for a customer base that is large, and that they’ll pay to solve that problem.

And in the baseball card space, it was a problem and people needed a way to store these cards. And some people wanted to store them in an archival safe way because they were going to be worth money. But a lot of them just wanted to store them. So, they didn’t really care, which is why a lot of competitors came out with cheaper products.

But in the case of Magic and these collectible cards, they were not only collecting, but they were like you said, playing them and in which case, you’re putting more stress on the sleeve and therefore you need to replace it. So, it was a better market in that sense, because people had a more acute pain and a more acute need that they had to continually pay for.

I didn’t put the dots together at that time that I was solving a better problem with a similar product, but it just proves that it’s really about finding the right market, the right customer that has this specific need and then building a product that solves that. That’s exactly what we did.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, that’s awesome. Can you think of any other examples of talking to people at trade shows or interacting with people that are using the product and, and sort of what I was trying to think, if you can like, maybe go through a story of like, yeah, someone came to the trade show and they said this, and then I talked to enough people that had that same issue, and then we made this product and it was either a success or not a success.

Just curious, like, if you have any examples of different stories that happened from that perspective.

Jeff Solomon: Well, when you’re doing this customer development, which is, talking to customers to find out their problems, a lot of times it’s less about what they say and more about watching and observing what they do.

And so, people would come, and they would tell me problems, but ultimately the biggest product that I launched, which is the one that I said, we’ve sold millions and, and is still being sold today, was largely from observation. And what I observed was that these kids that were playing this game would have our sleeves.

And when you buy the Magic cards, they come in a box. And in that box, it’s sized exactly for the card. But when you buy our sleeves, it also comes in a box. And that boxe’s slides ties to our sleeve, which is a few millimeters larger. So, you can’t put a card that has a sleeve on it in the original magic box, but you can put it in our box.

Our box was ugly, and our box was made of cardboard. And so, I saw all these people using these Ultra PRO boxes that came with their sleeves to store their decks. And their boxes were tattered, and they were ugly, and they weren’t effective, and they’d break down and they’d have to use a new one. And I thought, why not make a box designed specifically to store your deck, which ultimately became this thing called the deck box. And I wanted to build something that addressed the breakdown of the material issue. So, it had to be built in a stronger material. I wanted something that you could print. So, it couldn’t be like Lucite where it’s clear and you can’t really print well.

I wanted something you could print like high quality for color printing on. So, it had to be a certain kind of material. And so, we did the R and D to find flexible yet rigid plastic that could be printed on with offset printing, which is like printing on paper. So, you can get super high gloss, high quality print on the entire box.

And the idea that I came up with versus the other thing I noticed was that with a traditional box, the flap on the top folds inward, and that was bad because that could have the tendency to push on your cards or push on the sleeves. And so, it could damage your cards. And so, I thought, okay, the flap on the top needs to close on the outside somehow.

And so, I started thinking back to growing up when, in the eighties, when people still smoked. And I remember Marlboro and the rest of the cigarette companies, having these boxes where the flap opened on the top. I don’t know if you remember, like these little, flip up boxes that your pack of cigarettes came in and you could close it and it wouldn’t damage cigarettes on the inside.

I thought what if we could make it in that shape? So they did the R & D, and we found this plastic and we tested the printing and they were able to score the plastic in a way that they could make the top close and open that way with a piece of Velcro to hold it down. And we went to Magic, and I showed them the idea.

And I said, look, we can print your graphics all over these. And we can sell them. We can make six or seven different designs based on the current release art. And we launched that product, and it was a huge hit. Everybody had them, people were buying 5, 6, 7 decks or deck boxes. And then every quarter when Magic released their new graphics, we would print six or eight new ones.

So, there it was, it was like a collectible in its own way, and they looked amazing. And since then, there’s probably, if you go into any trading card store today, you’ll probably see the Ultra PRO deck box, but you’ll see dozens of other knockoffs that everybody’s done, everybody makes them now. And we sold, like I said, millions of those, and there’s probably been millions and millions more sold by other companies since then.

Brian Sierakowski: That’s such a great example. And I mean, it’s kind of a fortunate environment for you to be in because you can like physically observe people at these shows and you can watch people play Magic and you can, I’m sure you saw somebody with like their old crappy box that the, the sleeves came in and when they go to pick it up and all the cards fall off the bottom and like, um, okay it’s visible like how, how bad that is for them.

So, kind of, it’s such a cool example of being able to just like, watch your customers and understand the pain points. And, and maybe to your point, maybe they didn’t think that was a problem. That was just say they, they thought that was fine, but once you sort of solve the issue and then give them a better solution, you have pretty high confidence that something like this is going to be way better and sort of matches the behavior that we see everybody doing already.

Jeff Solomon: Exactly, I mean, that’s the art of this customer development effort is you can’t just ask someone what their problem is. Nine times out of 10. They’re not going to be able to tell you. So, if I had said like, hey, what’s the problem here. They’d be like, I don’t have one. But when I observed them, they actually showed that they did have a problem.

It didn’t work well, there was a workaround, but it didn’t really achieve the goal right. And so, when I finally put a product that solved that problem in their hands, they were like, oh my gosh, this is so much better and that’s the key. And a lot of founders, I think, make this mistake. When they’re launching their business, they come up with a problem and a solution, and then they either go to the market and they say like, hey, do you have this problem?

And then nine times out of 10, someone will say, yeah, I have that problem. And then you launched the product, and you find out like, actually they don’t really have that problem. They just said they did because it sounded obvious, but it really wasn’t acute. Or you’ll go to the market, and you’ll say, hey, what’s your problem?

And they won’t be able to tell you that because they can’t articulate it. They don’t see it that way. And so, the art is in extracting that by asking the right questions and doing the right observation to lead you as the entrepreneur, to come up with a solution that actually meets that need. It’s very challenging.

That’s the main reason I think why startups fail is they are unsuccessful at that effort or, or frankly don’t even attempt to do it.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah from the spot that I sit in, kind of seeing, understanding the finances of a lot of startups and sort of the shape and the trajectory of which they go through. I totally agree with you.

I think there’s a couple of like gates on forming a company. And I think the first is that you were already beyond this, by the age of five, you were actually getting started and actually taking action. Getting things out of the idea stage and getting them into the real world is a big gate.

And I think being able to build something functional is a huge gate. And then kind of what you’re discussing here, maybe I’m getting a little bit over the kind of concept of like product market fit, because I think that phrase has maybe gotten past its usefulness, but building something that solves a problem that people want to pay for is a huge game.

And then I think even beyond that, okay, well, we built something that’s really useful that solves a meaningful problem, but how do we get it to people? What does distribution look like? So, I think this is why, you frequently see, serial entrepreneurs even as they’re thinking about the thing that they’re going to build next, they’re already considering things like distribution, which maybe comes along too with doing really good customer development of understanding.

Okay, well, is this a problem that people have that they want to solve, but who are they and where are they at? How can I find them? And, uh, are they willing to pay money for this? It seems like there’s a lot of, again, it kind of goes back to the whole topic that we are the whole, whole thing that we’ve been discussing.

If like, there are all these sorts of skills that need to be developed that are very hard to train in isolation, but are really important to be successful in the long-term.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, I agree with you. There’s a lot of gates and each one of them is nuanced and hard to train and takes experience but I think this, my personal path is, is a good one for people to see that you don’t necessarily have to work for Google to learn those skills and then apply it to your startup. Like, I’d say if you did work at Google, you’re probably going to have a higher probability of learning certain skills that will apply to launching your own business than if you work at some plastic manufacturing company, but not necessarily, right?

You can acquire those skills in a lot of different ways, which is something I did, I didn’t plan it. And maybe there’s an easier, softer way, but yeah, I think the experiences you go through and connecting those dots can get you those skills to push through each of those gates that it requires to launch a business.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, I think that’s a good segue to take us to your kind of, next startup experience of building the company with the gaggle of founders and maybe, maybe not being as successful as you would have wanted. How did your experience go from Ultra PRO to that company? What was that shift like for you?

Jeff Solomon: A lot of it was driven by ego which is not a great way to run your life in general, but also not a great way to build a business. I felt good about myself, which was the healthy thing. I felt good about that experience there. I had joined another startup that had some success and I made some money.

And so, I was feeling pretty good about myself, but I really had not made the connections between what I had learned and how that could be applied to starting a business. I was just like, oh, I must be awesome. So, I can start a business. And it will work was my assumption. And so when I gathered these friends together and we went to go create something, we didn’t really do any of that work to find out what people actually wanted or what we could do that might meet a need in the market.

We were just like, hey, let’s build something cool. That sounds neat and there were a lot of companies doing that at the time. And a lot of them ended up being successful just because it was that time of the tech arc where things that were not really that useful ended up still getting big.

But at the end of the internet bubble, we didn’t have that momentum, that market momentum. And because we weren’t really meeting a real need, it just sort of failed. And that was pretty painful from an emotional standpoint. Like it kinda took its toll cause it knocked me down and I was like, hey, I’m kind of invincible.

I’m like amazing, I can build anything. And then we launched this pretty cool piece of software, but it just didn’t have a place? And it didn’t really do anything that people needed and people at that time when it was going from, hey, I don’t care what it does. I just want to be part of this whole internet thing to actually use this internet thing, but I’m not really going to participate unless it’s useful to me.

And so, products like Google obviously did really well during that turn because it was like, I need to use the internet and Google solves a real freaking problem. I’m going to use that product. And people became more like that. And we weren’t doing that and it just kind of fizzled out and we’d raised a little bit money, raised a few hundred grand and we built some great tech.

I had a couple of really good engineers, and we built some cool stuff, but it fizzled out and it, like I said, took a big emotional toll on me. I was kind of like, oh wait, what? I thought everything was all good. Why isn’t this working? And it took several years after that before I started to build back up my confidence that I could launch a business and grow a business and try again.

And it damaged a lot of relationships, like that one friend that I was best friends with in high school. We talk from time to time, but it was never the same. And he lived with me for like four years after college. And we were really close and that just permanently damaged that relationship unfortunately.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, it sounds pretty traumatic. Frankly, it’s interesting just with the arc of going through school and failing like, ah, geez. Like I’m dumb or I’m not the right shape for this world. And then you get into college, and you start to get a couple of little breadcrumbs of like, oh cool.

I can pass English and okay and I can have a good time and make friends and so you’re on this upward swing and then you have the experience at Ultra PRO and that goes really well. And you’re like, wow, we’re able to have this huge effect. And so, I can definitely see, it’s like, if you were low and then you were kind of ramped up and then I totally appreciate why you felt invincible.

And then you started this company and you’re like, yeah, this is going to be exactly like what I did at Ultra PRO, but bigger and better. And then it, it wasn’t, it was like, oh man, I can totally see. What were the next couple of years, like for you as you tried to rebuild confidence from there?

Jeff Solomon: Well, I definitely wasn’t of the mindset wanting to start another startup at that time. And I later now know that like there’s ups and downs, even in post big success with startups and exits, there’s still been failure too. So, I now sort of ride the wave. That’s sort of something I’ve learned, but at that time I wasn’t aware of that or ready for that. And so, I did leave that experience knowing that I really liked technology and liked building software. One of the things I really didn’t like about Ultra PRO was the slowness and the analog aspect of it.

And I really fell in love with the idea of solving business problems with software. And so, I at least had confidence that that was a real thing. Regardless of if I could build a big business around it, I knew it was something I wanted to do. So, I just started consulting. I started taking on projects from my network that needed some kind of tech built.

And it was still early enough in the internet period that there weren’t a lot of people doing that well. And so, I was able to pick up consulting gigs where I would build whatever, sometimes it’d be just a website, but mostly I try to build tools, like little admin tools to solve business things.

And I got a couple of good clients that had successful businesses, but were doing things in an analog way and they wanted to do it in a digital way, and they would come to me, and they would explain their business and I would visualize in my head a tool and how to solve that with the actual tool.

And I’d have, I had these scrappy developers that would build these tools for them. And so, we had a dev shop, and that company was called Thinklogic. And I started to grow that and was making an okay living and started to get my confidence back that I was good at this. And I was building really useful stuff that was solving specific problems.

Now they were solving problems for one company. They were very unique for those companies. So, there wasn’t a scalable business there and I still wasn’t even, I still hadn’t made the connection that like you had to, to build a company, you had to build a product or service that met the needs of a large audience in order to grow.

I had definitely realized that in order to make money, you have to build something that is useful and solves a need for somebody which I was now doing on a one-off basis. But I still hadn’t made that connection. And it really wasn’t until the one friend from that startup that failed that we remained friends, tight friends, who incidentally, we were not close to before.

He was the one person that kind of got brought in that I didn’t really know. He went to college with that one, buddy. There wasn’t a lot to damage there when it fell apart. So that one worked out good, and he was an engineer, and he went to get his MBA. During that time, after that failure, he’s like, I’m going to go back to business school and figure it out.

And so, he came out, he was doing some contract work for me. And he had learned in business school that one missing element that I didn’t know, which was, you can build things to solve problems, but you want to do it at scale. You have to solve it for a lot of people with the same product. And so, he encouraged me to start thinking about what I was building in that way.

And so, for the next six months, I started looking at everything I was building, and I started to see there were some trends and some similarities across clients where I was like, oh, well this client, this client, and this client all have this one similar issue. And the tools I built for them, they all, they solve different stuff, but this one piece is actually consistent among all three.

And that was a clue that maybe more customers or more, more companies out there had this one problem. And that, that was ultimately how it was born, because we realized that there were actually a lot of people, a lot of companies out there that had this, this particular sales related management issue, this CRM kind of issue that we ended up building a product for.

Brian Sierakowski: Cool, tell me more about that experience with Velocify.

Jeff Solomon: So, as I started to realize that, and, and my buddy Charles kept saying like, yeah, let’s build a SaaS business. I didn’t know any, I didn’t know what a SaaS business was. He was like, where you make a piece of software and instead of them paying you 20 grand to build it, they pay you three grand a month to use it.

And that really resonated. I’m like, oh, that’s cool. Because it only really costs a bunch to make it at first. And then if you can get people to keep paying you to use it, that’s way better business, that clicked. And so, I told him and a couple other guys like, hey, there’s this one piece that we’ve been building for these different clients that is consistent.

And I’m thinking maybe this could be the SaaS business you’re thinking about. And we did some more research on the market, and we basically came to the conclusion and here’s where timing is a huge factor, right? There are so many gates, like you said, you have to go through to launch a business that works.

There are all these factors, but one other factor that you can’t really control is timing of the market. And at that time, one thing was happening. That was just a perfect storm, in which the mortgage industry was on fire. And I mean, ironically it ended up being almost the reason that we went under, like we almost went under years later in which I’ll tell that story.

But at that time there was this whole subprime thing where people were just refinancing their homes or getting loans and mortgages. The mortgage industry was on fire. And I didn’t know anything about the mortgage industry, but I realized that we had like six of these mortgage companies as clients.

I didn’t put two and two together until that moment. And I realized that they all have the same problem of him getting all these inquiries from consumers that are wanting to refinance their house. Because rates are so low and rates have these special subprime mortgage models that turned out obviously to not work, but at the time it was like, oh, this is awesome.

Like the customer gets money and we make a huge fee and everything’s great. And so, these guys were getting all these inquiries and they started, all these lead gen companies started popping up like LowerMyBills and LendingTree. And all these guys were generating these leads for these mortgage companies, and they couldn’t hire mortgage loan officers, brokers fast enough.

And this perfect storm, especially in southern California, was growing, and they had no tools to manage this high volume of consumer increase, these consumer leads. And so, we built the SaaS tool, which was called Lead 360 at the time to manage those high numbers of leads. And it was designed to allow a company to have, in some cases, hundreds, or even thousands of people working phones, getting inquiries and managing these prospects as efficiently as they could such that they closed more deals. And so, it had a direct impact on their bottom line. Like if they use our software, they make more money. It was just like; it was that simple.

And so it was easy to sell, and we had a lot of data to prove that it actually worked. And we rode that wave and grew really, really fast on the backbone of that market trend.

Brian Sierakowski: That’s awesome, that sounds like you got yourself back into that similar spot of being able to find the trend and this time you used your own, the data that you had from the consultancy experience to start to push you in that right direction.

And then you were able to use your market census to say, oh, okay, well, this is coming, and you even mentioned like, oh, we even have customers currently that have this problem. And you’re able to push that forward into a solution that really had like, not necessarily an easy pitch, but you could, you could make the argument of like, hey, if you use this, you will make more money. And companies are generally pretty willing to listen to that.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah, yeah, I mean, that was, it’s still challenging. It wasn’t like, uh, we called them up and they sent us a check. Although there was a period probably of six or nine months where it was that easy.

But at first it took some convincing and explaining and showing, and the product was very basic. And over time, as we learned what the needs were and we built more features and we really tailored the product to the need, we became the de facto tool that you used. And incidentally, one thing that happened, which ended up being a great learning experience.

And I, by the way, I was now of the mindset that I had done enough of this sort of work where I didn’t know why things were working. Like now I was kind of connecting the dots better. So, it was like, okay, let me be a little more pragmatic about this. Like, okay. That connects with that. Like I see this.

So, I was starting to become a real entrepreneur by now. And what happened was really exciting. It related to the sales process, these companies that were generating these leads, like LendingTree. They would, someone would go on, lendingtree.com and banks compete, and you win. That was their host logo slogan.

And a consumer would fill out a form, a little form saying they want to refinance their home. They put in some information and then LendingTree who built a brilliant business model to the whole legion model. They would then say, okay, Mr Homeowner, you want a loan? I’m going to send your lead to five of our clients, five different mortgage brokers or mortgage companies that are essentially selling the exact same product.

They’re going to fight to get your business and that seemed like a good pitch to the consumer. And to some extent it was a good pitch. Although later it became more of a headache for consumers then, at that time it was great. And then they basically were capitalizing on one lead being sold to five companies and they didn’t really care what happened after that, but LendingTree and particularly LowerMyBills, this guy, Matt Coffin, was running this company LowerMyBills who turned out to be a genius entrepreneur.

And I learned a lot from, and he was kind of a mini mentor to me. He came to the conclusion because he saw a problem in his own business that he would sell these leads to five mortgage companies. Those mortgage companies sucked at closing those leads because they weren’t using a product like ours and they would call up LowerMyBills, and they’d say, these leads are bad. These leads don’t close. Like I don’t, I don’t want to be a customer anymore. And he was like, no, they’re not, they’re not bad. And then he would dig in and he found that these people, these loan officers and these mortgage companies, weren’t actually calling the leads, they’d get a lead and would just sit there because they were just overloaded.

And so, he came to the conclusion that like, hey, if these guys had a tool that actually helped them follow up on these leads, they would close more, and they wouldn’t have tripped. So that guy then went to the market and started looking for a tool. He didn’t want to build one. He’s like, somebody’s got to be out there doing it.

And he found us and we kind of knew about him at the same time because our clients were buying from LowerMyBills. And so, we started talking and he said, we’re going to promote you guys. We’re going to tell our clients to use your tool. And for those next six months, every time LowerMyBills would get a new customer, a new mortgage officer, a new mortgage company would come to them to say, hey, I want to buy your leads.

They would say, and they literally said this for like six months until they didn’t want to be completely in our boat. They said, I will not sell you leads until you implement Leads 360. I don’t want to waste my time with you. It’s a waste. So that was like, okay, he’d send us the referral. We’d sign them up three days later, they’d beyond.

And then they’d be getting leads and everybody won. And so, for those six months, it was literally like a one-call close. Like, hey, I’ve got a new client, they’re about to come on, LowerMyBills. Okay, cool. Set them up.

Brian Sierakowski: Right.

Jeff Solomon: You know.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, that’s awesome.

Jeff Solomon: That was like the ultimate partnership.

Brian Sierakowski: Yeah, what a win-win they’re in the spot where it’s like, well, if they don’t make you money, they make less money.

So, it’s like, well, yeah, of course I would do this. And they had I think that’s like a really sharp entrepreneurial tendency. Because I think a lot of people would want to build that system themselves, but they thought about it intelligently. I think like, well, we can decrease our churn for $0 and we and like zero time, if you already had the system set up, you were already doing well and you were already in space.

So yeah, what a smart partnership that I’m sure you were thrilled to engage in as well.

Jeff Solomon: Yeah it was great, and I, incidentally, I learned a really interesting thing that I’ve shared with entrepreneurs and students in that, business development partnerships regularly and most of the time fail.

And I see this all the time with companies like, oh, how are you going to grow? Oh, we’re going to do a partnership with this other company. And they’re going to help us grow. And my sort of feedback in my experience has been that even if a partner of yours sells to the exact customer, you want to sell to, so you’re talking to the company, whatever, and they are selling their product or service to the exact person that you want to sell your product or services to.

It seems logical that if they became your partner, they could also either sell your product to their customer or refer you to their customer. But the problem is, even though that is true, the problem is that unless what we bring to the table actually helps that partner do their business better.They’re not going to get behind the partnership. It’s just a distraction.

Even if you say, look, we’re going to pay you $500. Every time we bring on a client, it’s not significant enough because their primary goal is to sell their product or service better or more or reduce churn or whatever, you have to play into that.

So, when I look at partnerships now, I basically say no to any business development partnership unless the partnership helps them do their core business better. And unfortunately, that’s a rare alignment. It doesn’t usually align. And so, I say no to a lot of business development relationships because of that, because they’re just not going to work.

It’s not a good use of time, but in the case of the LowerMyBills and LendingTree one, our product did help them do their business better. They reduced churn, they made more money. So, it was like a clear, clear, perfect fit. So, I really look for that now when I think about business development partnerships.